The blog post for this week has been written by Tom Hardwick, an Egyptologist and curator. He has worked with Egyptian collections in the UK, USA, and Egypt. He is a specialist in pharaonic Egyptian sculpture and iconography, and has worked extensively on the history of collecting Egyptian objects.

The centenary of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, coming up in

November, overshadows a rather more niche anniversary occurring this week and

last: the hundredth anniversary of the sale at the auctioneer’s Sotheby’s of

the Egyptian collection of the Revd William

MacGregor (1848–1937), Vicar of Tamworth 1878–1887 (fig. 1). The dispersal of MacGregor’s

collection would turn out to be a boon for the Egypt Centre, as Ken’s tweetalong

to the sale has been showing. It was also the unwanted end to almost a year of

negotiations between the collection’s owners and some of the wealthiest men in

the world.

|

| Fig. 1: William MacGregor |

MacGregor came from a monied background, so could afford to visit Egypt

in 1885 to convalesce from an illness. Bitten by the Egyptological bug,

MacGregor became a keen supporter of the young Egypt Exploration Fund, even

helping the Fund’s senior excavator Edouard Naville in some of his excavations

in the Delta.

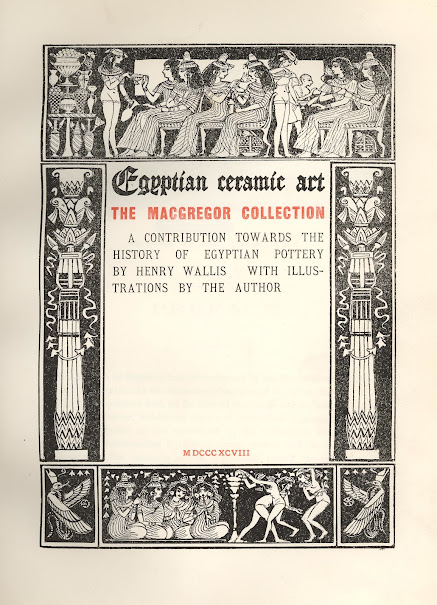

MacGregor’s interest in ancient Egypt and its antiquities was not an abstract one. As did many other visitors to Egypt at the time, he formed a collection of Egyptian objects, taking advantage of a legal (or semi-legal) trade in antiquities in Egypt that would not be abolished until 1983. MacGregor’s collection grew steadily, fuelled by suppliers like Henry Wallis. A successful member of the Pre-Raphaelite painter in the 1850s and 1860s, renowned for his Death of Chatterton, by the 1880s Wallis was a seasoned traveller in the Mediterranean and Levant, where he would paint watercolour scenes full of local colour to sell back in London. He also collected and studied ceramics on his travels, writing a number of studies that gave prominence to objects he owned or had just sold. Wallis was what one would now call an art influencer, making his way by buying, publishing, promoting, and selling on collections. From the mid-1880s Wallis had started to lend Egyptian “ceramics”—most not pottery, but what Egyptologists call faience—to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). In 1895 he ended the loan to lend many of them to an exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, a private club for collectors and “connoisseurs” of art. While we now take touring exhibitions of Egyptian objects for granted—Tutankhamun, Ramesses, Cleopatra all in recent years—the 1895 exhibition was the first temporary exhibition to bring together and display Egyptian objects as artworks. Wallis and MacGregor did not just lend objects from their collections, but served on the organizing committee alongside his fellow collector Frederick Hilton Price and Egyptologists like Adolf Erman, Flinders Petrie, and Gaston Maspero.

|

| Fig. 2: Egypt Centre W424, as illustrated by Wallis, and now (the stand is a modern addition) |

The exhibition was well-received, and MacGregor celebrated the

vindication of his taste shortly afterwards by buying many of the objects

Wallis had put on loan (fig.

2). Wallis fulfilled his part of the bargain by publishing a history of Egyptian

“ceramic art” centred on MacGregor’s collection (fig. 3), which he claimed was of a quality

that “permit[s] the opportunity of taking a comprehensive survey of the

progress of the art of the Egyptian potter from an early period up to that of

its latest development, such as is scarcely to be found elsewhere.” Wallis

continued to collect and write on Egyptian art, and produced a second illustrated study

of “ceramics” in 1900. Wallis

later sold some objects in this to MacGregor, too.

|

| Fig. 3: “Henry Wallis’s Egyptian Ceramic Art (1898) |

Another of MacGregor’s suppliers was Count d’Hulst,

whom MacGregor had excavated alongside in Egypt. Around 1896, d’Hulst sold MacGregor

a small but exquisite obsidian head of a king for the then sizeable sum of

£100; this would soon become widely regarded as the gem of his collection (fig.

4).

|

| Fig. 4: Obsidian head of a king, acquired by MacGregor in 1896 |

MacGregor also acquired objects as a quid pro quo for funding excavations, in particular those of John Garstang in Egypt and Sudan, to which he provided significant support. His collection, therefore, contained excavated archaeological material alongside purchased material with no documented findspot. By 1921 he owned thousands of objects, displayed in the “museum” at his house Bolehall Manor. While Wallis’s publication and the Burlington exhibition focused on individual, beautiful objects, it’s clear that MacGregor’s collection was not—could not be—limited to this, and contained what he and his contemporaries would have called many “series” of object “classes.” These could be different objects made from the same material, different materials used to make the same type of object, the same type of object from different sites, or numerous representations of the same deity or amulet. Even if they weren’t easy on the eye, many of MacGregor’s objects would have had a meaning and importance to him, and its own place in his museum.

In addition to Wallis’s published catalogues, MacGregor himself organized his

collections. Contemporary letters reveal that he compiled a card catalogue and

several volumes of photographs, now lost—and one of the great what-ifs of the

history of Egyptology. Some sense of the scope of his cataloguing can still be

encountered on objects he owned: many of these still preserve numbers on them

which presumably derive from his inventory of his collections. These are either

written directly on the object in his distinctive vertical hand, or printed in

red ink on plain paper labels (figs. 5–6).

|

| Fig. 5: Egypt Centre W399 with the handwritten MacGregor number 3940 |

|

| Fig. 6: Egypt Centre W932 with MacGregor's printed collection number 1723 |

Twenty-five years after the Burlington Fine Arts Club’s Exhibition of the Art of Ancient Egypt, the Club decided to put on another exhibition of Egyptian objects (Pierson 2019). MacGregor again lent objects and served on the committee of the Exhibition of Ancient Egyptian Art, which ran from May to July 1921. He was the only survivor of the 1895 exhibition committee (although Petrie’s collection at University College London also lent objects), which now contained a new generation of collectors and Egyptologists such as Lord Carnarvon, Howard Carter, Percy Newberry, and Richard Bethell. MacGregor’s objects were central to the success of the exhibition, none more so than his obsidian head, then identified as the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Amenemhat III and now as his father Senwosret III. Reviewers acclaimed this as “one of the supreme masterpieces of the exhibition” and “almost the finest piece in all Egyptian art.”

For MacGregor, all publicity was good publicity: he had decided to sell

his collection during the run of the exhibition, and praise like this would

help him get a good price. If he decided to sell in summer 1921, though, why

did it take a year for the collection to come up for sale? The answer is that

MacGregor didn’t consign it to auction: he sold it to the art dealer Spink and Son in 1921, and Spink then took

the better part of a year to shift it. Founded in 1666 as a goldsmith’s, by the

start of the twentieth century Spink and Son had a royal warrant to strike

medals, a shopfront on Piccadilly Circus—the heart of empire—and dealt in

numismatics, pictures, Oriental (i.e. Chinese and Indian) art, and antiquities

(fig. 7).

|

| Fig. 7: Letterhead of Spink and Son, 1922 |

Spink’s monthly publication the Numismatic Circular offered descriptive listings of coins and medals for sale alongside notes and news from the numismatic world, and their specialist, Alfred E. Knight, had compiled several selling catalogues of antiquities along similar lines, in addition to Amentet, a guide to Egyptian amulets explicitly written for collectors, coincidentally jammed with puffs for Spink’s own stock. Spink felt they had the experience and client list to turn a profit on MacGregor’s collection, so took out an option on it for £20,000, to be paid by the end of 1921.

Spink then tried to achieve any dealer’s ultimate goal: to sell

something before you have paid for it. Archives spread around the world—Spink’s

own archives, sadly, were lost in the Blitz—give some sense of what happened next.

Lord Carnarvon, whose own collection had also been admired at the Burlington

exhibition, was approached about it. He and his adviser, Howard Carter, seem to

have contemplated buying it, or selling it on to another collector, in

conjunction with Carnarvon’s friend Richard Bethell. At the same time, Spink

had put Percy Newberry, former Professor of Egyptology at Liverpool University,

on commission to sell the collection (one wonders which Professors of

Egyptology would do the same today?). Carter and Newberry fell out over the

resulting mess, while Newberry made a fruitless trip to Chicago to attempt to

sell the collection to James Henry Breasted’s Oriental Institute, then flush

with money from oil magnate John D. Rockefeller.

But how much was the collection worth? Spink was put in the difficult position

of trying to value something that was both unique (the obsidian head) and

commonplace (the vast quantity of amulets, pottery vessels etc). After World

War I the art market boomed, with American buyers snapping up European

treasures through the intermediary of dealers such as Sir Joseph

Duveen. The Duke of Westminster had just sold Gainsborough’s Blue Boy for

an astonishing £125,000—what was the right price for the obsidian head,

something much older and rarer, but much less securely identifiable as “art”?

Spink alerted dealers, “runners” like Carter and Newberry, and offered the

collection directly to wealthy collectors like American industrialist Theodore

Pitcairn and William Randolph Hearst, the American media mogul (and model for

Citizen Kane). Early offers of the collection priced it at £65,000, with the

head said to be worth £30,000 on its own. These were doubtless only intended to

be starting points for negotiation, and later offers fell to £45,000 for the

whole collection or £20,000 for the head, and finally £35,000 for the whole

collection. No one wanted it.

Spink paid MacGregor at the end of 1921 and shipped his collection to their

London galleries, where Alfred E. Knight, with some assistance from Percy

Newberry, began to catalogue it. With no takers for the collection en bloc,

Spink decided to sell it at auction. The auctioneers Sotheby Wilkinson and

Hodge were the obvious choice for the sale. Although they were further away

from Spink’s offices than their rivals Christie’s, Sotheby’s had handled many

of the previous major Egyptian sales, such as those of F. G. Hilton Price in

1911 (where MacGregor himself had purchased a number of objects) and Lord Amherst

during the Burlington exhibition the previous summer. The MacGregor collection

was larger than either, and was organized into 1800 lots, containing over 9,000

objects, sold over nine days (fig. 8).

|

| Fig. 8: Title page and frontispiece of the MacGregor sale catalogue |

I’ve written popular

and academic articles on the MacGregor sale elsewhere (Hardwick 2011; 2012).

What is noticeable is that while the sale’s total of £34,092 came close to the

£35,000 Spink wanted for the whole collection, much of this was achieved by

Spink’s own agents bidding on their own objects to drive the price up. In many

cases the other bidders lost interest and Spink was left with its own objects,

“bought in” as the term has it. Spink was the second-largest spender at the

sale—spending almost £4,000—and the largest purchaser by number of lots (nearly

25%). While Spink’s unexpected purchases were not the end of the world—they

would give it an impressive stockroom for future sales—once these were taken

into account, along with the auctioneer’s commission, the price of the

catalogues, the fees to Newberry and others, Spink’s profit on the £20,000 it

paid MacGregor was much less impressive than they had hoped for. Even though

the £10,000 fetched by the obsidian head, which was sold to the oil magnate Calouste

Gulbenkian through an elaborate series of false names and handkerchief

signals, was the largest price fetched by an Egyptian object, it was far from

the £30,000 it was initially proposed at—and a twelfth of the astronomical

price of the Blue Boy. Egyptian objects were not valued on the same

terms as Western works of art.

Every cloud had a silver lining, though: for Sir Henry Wellcome, the fact that

the MacGregor collection was set to be dispersed at auction gave him the

opportunity to bid on objects for the Historical Medical Museum he had already

been building for nearly twenty years. Wellcome was notoriously keen on a

bargain, and buying at auction removed a dealer’s markup. Wellcome and his numerous

agents were the most prolific (genuine) purchasers of objects at the sale,

buying over 20% of the lots containing 25% of the objects … for under 5% of the

price! Other MacGregor objects would make their way into Wellcome’s collections

until Wellcome’s death in 1936 brought his collecting to a close. Wellcome’s

purchases from the MacGregor collection, at the cheaper end of the spectrum,

did not include many masterpieces, but reflect the range of MacGregor’s tastes.

Ken’s live-tweeting of the sale, seen through the lens of the Egypt

Centre’s holdings, gives some sense of what must have been an action-packed

two weeks!

Bibliography

Burlington

Fine Arts Club 1921. Catalogue of an

exhibition of ancient Egyptian art. London: Burlington Fine Arts Club.

Burlington

Fine Arts Club 1895. Exhibition of the art

of ancient Egypt. London: Burlington Fine Arts Club.

Hagen,

Fredrik and Kim Ryholt 2016. The

antiquities trade in Egypt 1880-1930: the H.O. Lange papers. Scientia

Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 8. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Danske

Videnskabernes Selskab.

Hardwick,

Tom 2012. The

obsidian king’s origins: further light on purchasers and prices at the MacGregor

sale, 1922. Discussions in Egyptology 65, 7–52.

Hardwick,

Tom 2011. Five

months before Tut: purchasers and prices at the MacGregor sale, 1922. Journal

of the History of Collections 23 (1), 1–14.

Pierson,

Stacey J. 2019. Private collecting, exhibitions, and the shaping of art history

in London. The Burlington Fine Arts Club. London: Routledge.

Rogers, Beverley 2010. The Reverend William MacGregor: an early industrialist collector. Antiquity 325.

Sotheby,

Wilkinson and Hodge. (1922) Catalogue

of the MacGregor collection of Egyptian antiquities. London: Davy.

Ricketts,

Charles 1917. Head of

Amenemmēs III in obsidian: from the collection of the Rev. W. MacGregor,

Tamworth. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 4 (2/3), 71–73.

Wallis,

Henry 1900. Egyptian

ceramic art: typical examples of the art of the Egyptian potter. London:

Taylor & Francis.

Wallis,

Henry 1898. Egyptian

ceramic art: the MacGregor collection; a contribution towards the history of

Egyptian pottery. London: Taylor & Francis.

Fascinating and informative article, thank you

ReplyDelete