In last week’s blog post, I presented the back panel of a Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure (W2052). This is one of twenty-nine objects in the Egypt Centre collection, which have been categorised as Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figures: twenty figures and nine headdresses. While photographing some of these items last month, I was particularly intrigued by one of the headdresses (W2062). The object is a typical example of the Ptolemaic Period and may not seem to be overly exciting. It is made of wood, which is covered in a layer of painted gesso. Measuring 202mm in height, 169mm wide, and 22mm thick, the headdress was clearly part of a large Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure (fig. 1). The ram’s horns are painted black, while the double features have blue, red, and green decoration on a cream background. A yellow sun disc is painted on the front.

|

| Fig. 1: Ptah-Sokar-Osiris headdress (W2062) |

So what makes this headdress so interesting? Well, when

checking the data on the Egypt Centre’s catalogue, I noticed that it had an

unidentified number 118 associated with it. As the catalogue had no further

details about this number, I checked the object file to see if there was

anything additional, or even if the label with this number still existed. Fortunately,

it did, with the style indicating to me that it was a lot number (fig. 2). This

is not surprising since much of the Egypt Centre collection originated from

that of Sir Henry Wellcome, who purchased innumerable Egyptian objects at

auction for over three decades until his death in 1936.

|

| Fig. 2: Archives from the object file, including lot label |

With no further details on the label, surely it would prove

difficult to identify the specific auction? While the label may seem somewhat

generic, I knew it was a type commonly found on objects from the 1907

collection of Robert de Rustafjaell, which was auctioned by Sotheby’s.

Therefore, I checked lot 118 in the auction catalogue to see if the description

matched. Bingo! My hunch proved accurate, with the catalogue describing the lot

as “Another of similar size, the base shorter [Plate VIII]”. The preceding lot

was a complete Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure, which also happens to be in the Egypt

Centre collection (W2001C).

Most exciting is that a photo of W2062 is shown in the plates, but as a

complete Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure rather than just the crown of a figure (fig.

3)!

|

| Fig. 3: Plate VIII showing lots 117 (W2001) and 118 |

I checked the Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figures in the Egypt Centre

collection to see if any matched the plate, without success. Knowing that the

Egyptian material in the Wellcome collection was dispersed to several UK

institutions, I messaged Dr Ashley Cooke, the lead curator of antiquities in

the World Museum

Liverpool, to ask if the Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure was in Liverpool. I

received a reply within an hour, with Ashley suggesting that it could be

acquisition number -. This object is a tall and slender

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure on a base, which, stylistically, comes from Akhmim

(fig. 4). A comparison between the photos provided by Ashley and the plate

confirm a perfect match. Readers to this blog are probably wondering about the

Sokar-hawk, which is shown on top of the base on the Liverpool object but not

in the auction catalogue. It turns out that this Sokar-hawk is a recent

addition, which carries a different acquisition number.

|

| Fig. 4: Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figure in Liverpool (1973.1.686) |

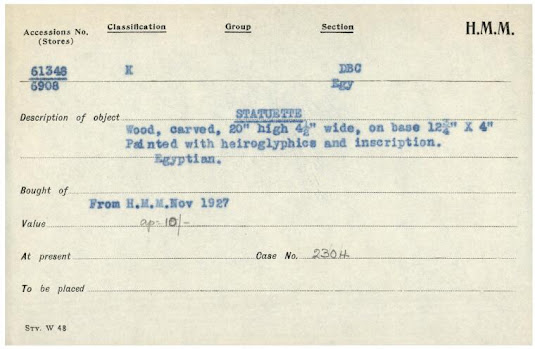

So how and when did the crown become separated from the

figure and base? While it is not possible to say with any precision, it can be

determined that this happened sometime between 1907 and 1927. The Wellcome

number associated with the figure in Liverpool is A61348 (fig. 5), which

describes it as a “STATUETTE. Wood, carved, 20" high 4½" wide on base

12¾ " x 4 Painted with heiroglyphics and inscription. Egyptian.” This

roughly matches the measurements of the Liverpool figure, indicating that the

headdress in Swansea was no longer associated with it when the object was

catalogued at the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in 1927.

|

| Fig. 5: Wellcome slip |

This blog post highlights the importance of collaboration

between museums with Wellcome material, which can often lead to understanding

our collections better and even virtually reuniting objects. I am most grateful

to Ashley for providing information and photos of the figure in Liverpool.

Bibliography:

Bosse-Griffiths, Kate 2001. Problems with Ptaḥ-Sokar-Osiris

figures: presented to the 4th International Congress of Egyptology, Munich,

1985. In Bosse-Griffiths, Kate, Amarna studies and other selected papers, 181–188. Freiburg (Schweiz); Göttingen: Universitätsverlag;

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Raven, Maarten J. 1978–1979. Papyrus-sheaths and

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris statues. Oudheidkundige mededelingen uit het

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden 59–60, 251–296.

Raven, Maarten J. 1984. Papyrus-sheaths and Ptah-Sokar-Osiris

statues [+ corrigenda]. In Symbols of resurrection: three studies in

ancient Egyptian iconography / Symbolen van opstanding: drie studies op het

gebied van Oud-Egyptische iconografie, 251–296, xi. Leiden: Rijksmuseum van

Oudheden.

Rindi Nuzzolo, Carlo 2014. Two Ptah-Sokar-Osiris figures from Akhmim in the Egyptian

collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Bulletin du Musée Hongrois des Beaux-Arts 119,

13–41.

Rindi Nuzzolo, Carlo 2017. Tradition and transformation: retracing Ptah-Sokar-Osiris

figures from Akhmim in museums and private collections. In Gillen, Todd (ed.), (Re)productive traditions in

ancient Egypt: proceedings of the conference held at the University of Liège,

6th–8th February 2013, 445–474. Liège: Presses universitaires de

Liège.

Sotheby,

Wilkinson, & Hodge. (1907) Catalogue of a collection of antiquities

from Egypt, ... being the second portion of the collection of Robert de

Rustafjaell, esq. F.R.G.S, which will be sold by auction, ... on Monday, the

9th of December, 1907, and the following day. London: Sotheby, Wilkinson

& Hodge.