This semester our Egyptian Art and Architecture class (CLE220) has been lucky enough to have had a series of hands-on sessions with objects from the Egypt Centre, facilitated by the Collections Access Manager Ken Griffin. In these sessions, students are confronted with objects they have never seen before and about which no information is provided. In small groups, they try and find out as much about the piece as possible based purely on team-work, their own observations, and background knowledge acquired prior to the handling session via a preparatory reading and lecture. In follow-up seminar-style sessions, we usually summarise our observations as a class and try and identify the key features, date, and purpose of the piece. Occasionally, we will use these sessions to develop research and art-historical skills by conducting further research in groups on different aspects of a single artefact.

|

| Fig. 1: W802. |

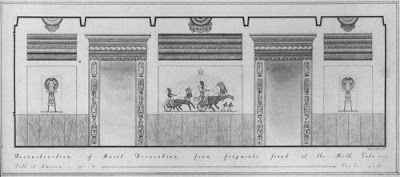

In the follow-up seminar, we broke up into three groups: one group looked at the find context, another at the design of the painted clothing, and a third group at the reconstruction of the scene element to which the fragment belonged. As the “context” group found out in the follow-up seminar, this was one of a number of fragments found in the debris of the gateway of the North Riverside Palace (Pendlebury, 1931), a huge residence linked to the main city by a processional road and that probably served as the main residence for the Amarna royal family (Kemp, 2013). The excavator, John Pendlebury (1904–1941), thought the decorated plaster was part of a decorated private room above the gateway, but it may have been part of the gateway. Other plaster fragments from the same context have cartouches of the royal family, offerings, and parts of chariots. Importantly, the context group also located a watercolour of the Swansea piece at the time of excavation showing details that are no longer visible (fig. 2).

|

| Fig 2: http://www.amarnaproject.com/images/amarna_the_place/north_city/15.jpg |

The group focussing on the reconstruction of the scene had a very difficult job. They agreed that the elbow might indeed belong to a person holding the reins of a chariot, as originally reconstructed by Ralph Lavers (fig. 3), drawing on scenes from the Private tombs at Amarna. But they also thought it could just as easily be a person in a different pose, for example, a seated figure or a standing figure making an offering. Critically, they noted that Fran Weatherhead (2007) had previously observed that Laver’s reconstruction incorporated fragments reproduced at different scales!

|

| Fig 3: http://www.amarnaproject.com/pages/amarna_the_place/north_city/7.shtml |

But who is represented on the fragment? The work of the “clothing group” here provided some clues by looking in detail at the design of the polychrome pattern. The latter consists of a row of blue diamonds, either side of which there are seven zig-zag lines of red, light blue, and dark blue on a yellow-beige background. The upper and lower edge of the belt is framed by a band of chevrons drawing on the same palette. As one of our students Cameron Nairn discovered, the pattern of diamonds and zigzags is very similar to the design of a belt from a granodiorite statue in the British Museum (EA 5) depicting Akhenaten’s father, Amenhotep III (fig. 4), whereby that belt lacks the chevron-border of the Egypt Centre fragment. In fact, the Egyptologist Betsy Bryan (2007, 175) has argued that this belt design was the most common belt type on the royal statuary of Amenhotep III.

|

| Fig. 4: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=111353&partId=1&searchText=amenhotep++statue&page=1 |

Subsequent research showed that the belt with lozenges and zig-zag lines was much older than Amenhotep III, and it can be traced backwards through history, from the early New Kingdom (ie. Cairo JE 39260, http://www.ifao.egnet.net/bases/cachette/?ident=JE%2039260#galerie, Thutmose III), to the reign of Sneferu (Fourth Dynasty), if not earlier. As discussed by Nakano (2000), it was an iconographic element used solely for the depiction of Egyptian kings. While the precise symbolism of the pattern is unknown, it clearly alludes to the concept of kingship and helps identify the figure on the Egypt Centre fragment as a king, and not someone else. Who this pharaoh is can be guessed by the evidence for cartouches bearing royal names from the same context—it's possibly Akhenaten himself! That being said, the depiction of the king in this costume is rare at Amarna where the king was usually shown wearing a characteristic pleated, white kilt, that dipped sharply at the front to accommodate Akhenaten´s protruding belly (fig. 5).

|

| Fig. 5: Colossal statue of Akhenaten. |

One of the great challenges of working with Egyptian art is trying to imagine a three-dimensional artefact based on its two-dimensional depiction (Siffert). For example, what materials would the original have been made from? How do the smooth flowing brush strokes of the painting correspond to the texture of the original? Here the “Belt Group” had another break through. They came across an extremely rare piece of royal costume housed in the Liverpool World Museum (M11156) known as the Ramesses Girdle (fig. 6). The piece is a magnificent 5.2m long sash of woven linen with an intricate pattern of ankh signs and zig-zag lines in red and blue on a yellow-beige background that bears the name of Ramesses III. Although the piece was probably worn differently to the belt on the Swansea fragment, the palette of colours, the zig-zag lines and borders, and the yellow-beige background of the textile all reminded us strongly of the belt and helped us to imagine at least one way the polychrome painted plaster surface could be interpreted.

|

| Fig. 6: http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/wml/collections/antiquities/ancient-egypt/item-299418.aspx |

In the next weeks, we will be looking at more objects—stone palettes and decorated pottery—before turning to the architectural context of art. We will be finishing off the semester with talks and question sessions with people who have made careers in “Egyptian Art”. Chicago House staff artist, Krisztián Vértes (Chicago House, Luxor), will be talking about Digital Epigraphy, the conservator Suzanne Davis (University of Michigan), will present about “preserving Egyptian art”, and the architect Abigail Stoner (Berlin), will discuss recording Egyptian architecture.

Bibliography:

Bryan, B. M. (2007) ‘A ‘New’ Statue of Amenhotep III and the Meaning of the Khepresh Crown’. In The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor 1, ed. Z. A. Hawass and J. E. Richards. Cairo: Conseil Suprême des Antiquités de l’Egypte. 151–167.

Kemp, B. J. (2013) The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People. London: Thames & Hudson.

Kozloff, A. P., B. M. Bryan, and L. M. Berman eds. (1992) Egypt’s Dazzling Sun: Amenhotep III and His World. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press. Bloomington.

Nakano, T. (2000) ‘An Undiscovered Representation of Egyptian Kingship? The Diamond Motif on the Kings’ Belts’. Orient 35: 23–34.

Pendlebury, J. D. S. (1931) ‘Preliminary Report of Excavations at Tell el-‘Amarnah 1930–1’. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 17: 233–244.

———. (1951) The City of Akhenaten. Part III: The Central City and the Official Quarters. The Excavations at Tell el-Amarna during the Season 1926–1927 and 1931–1936. 2 vols. Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 44. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Siffert, U. (n.d.) From Object to Icon: Visual Reflections on and the Designations of Material Culture in the Reliefs and Paintings of Middle Kingdom Tombs (poster presentation).

Weatherhead, F. (2007) Amarna Palace Paintings. Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 78. London: Egypt Exploration Society.