The blog post for this week has been written by Iris C. Meijer. Iris lives in Luxor, Egypt, and has a deep passion for all things ancient Egyptian. She is currently owned by seventeen rescued cats and dogs and spends her extra time trying to raise awareness for animal welfare.

When we visit Egypt and walk through the vast pylons, columned courtyards and rooms of the temples there, the silent witnesses towering over us conjure up a world of mystic stillness and belief. Empty, they speak of a time when humanity worshiped on a broad canvas, leaving us monuments of such awe-inspiring dimensions that we forget that they were not always so quiet. We wander between the columns and enigmatic writings and depictions and forget to ask: what was it really like back then?

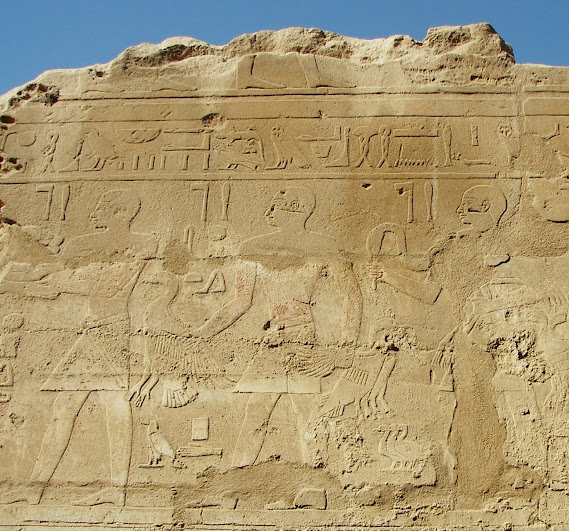

One thing we must immediately think of when we

contemplate such questions is the people. There must have been people doing

things in these major structures! And indeed, there were, and more than a few

of them. Priests and priestesses, servants, caretakers. High clergy, low clergy,

and auxiliaries (fig. 1).

An equally enormous workforce was needed to keep the gigantic cosmic machinery

that these temples were ticking over.

|

| Fig. Priests at Karnak carrying offerings |

You see, other than in most current religions, where

temple, church, and mosque are gathering places for people to congregate and

celebrate their faith together, the temples of ancient Egypt had no such

purpose. The temples of ancient Egypt were, quite literally, the houses of the

gods, their homes. The essence of the gods dwelled in the temples, and it was

that presence that the priesthood and every other person allowed to set foot

inside the hallowed walls were meant to serve. Nowadays, we translate their

title as priest or prophet, but the real, simple translation of their name ḥm nṯr was “servant of the god”

(fig. 2).

|

| Fig. 2: Priest of the Temple of Ramesses II at Abydos |

So we have a giant, vast mansion (or a smaller one)

meant to be the dwelling place of a god or a group of gods, staffed with

servants whose job description was to see to the divinity’s every need. A bit like

Downton Abbey but then the one being served was a divinity in statue form. And seeing

to their every need included waking them up in the morning, helping them wash,

dress, put on makeup, jewellery and ointments, and so on—in a ritual that had thirty-six

specific, core steps with their own “spells” or recitations for each step, with

a possible twelve more depending on which temple. It included making sure they

were fed with the essence of the best beef, fowl, bread, beer, fruits, and

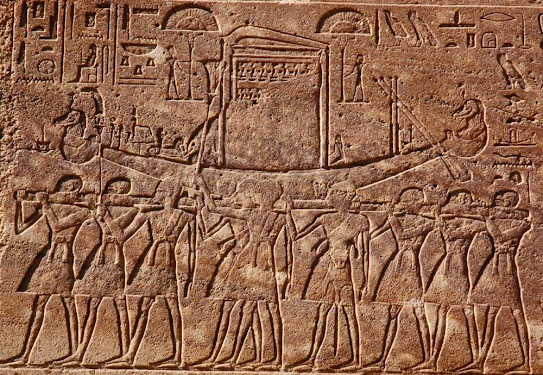

other good things the world had to offer. It included organising trips out into

the world, grand processions for great feasts where the whole populace would

come out to celebrate alongside the route (fig. 3). And it meant doing everything else that was

needed to keep the temple, the worship, and keeping the essence of the god on

earth and satisfied, going, with all that entailed. These servants of the god

and their subordinates were in charge of all that, but those, somewhat more

esoteric things were not even the only things that went on in the temples.

There was also simpler, more practical work to do.

|

| Fig. 3: Priests transporting the barque of Amun |

In the middle of each temple precinct, there is a

temple, made of stone. Big or small, the central building, the focus, the

dwelling place of the god was always made of enduring stone after a certain

time period. But there were usually also grounds and auxiliary buildings around

it, and these were often made of mud brick, a much cheaper, but also more

perishable material. So many activities took place there: school teaching the

offspring of the priests, baking of bread, slaughter of offerings, making of

offering bouquets of flowers, making of art and jewellery and much more—everything

practical that needed to be done to produce the end result of keeping the god

happy and in place (fig. 4).

The day-to-day management of the assets of the god took place there—including

scribal activity, accounting, overseeing the treasury, keeping track of taxes.

There was a continuous buzz of activity. For instance, it is estimated that in

the New Kingdom, the most important deity of the time, Amun of Karnak, owned

around 1/3 of the whole country in estates that went to feed the huge, ever-hungry machinery of Karnak Temple, and that over 80,000 people worked for the

temple and estates of Amun during the reign of Ramesses III! So we are not

talking just sleepy village chapels and priests, we are also talking about

giant, busy concerns who would at times rival the pharaoh in worldly power.

|

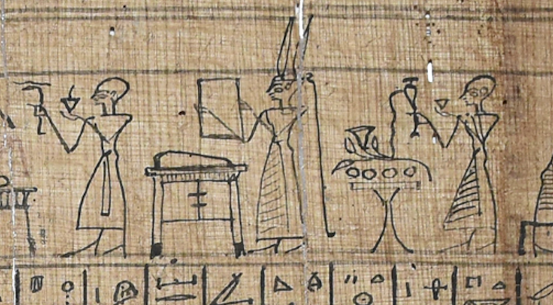

| Fig. 4: Food for the gods in the Tempe of Ramesses II at Abydos |

So much went on in the temple and its environs, it’s hard to encompass in one’s mind. All the above, and medical work, astronomy to know when the festivals should take place, architecture, and planning for the next embellishment of the mansion of the god, dealing with petitioners and the occasional oracle, the list goes on. And for all these, priests were needed. Many titles and specific functions have come down to us from those seemingly silent columns and walls, as well as papyri. And we still do not know everything, as the evidence is fragmentary and still being decoded.

We do know that the priesthood had levels and ranks,

and that this was very important. There were the servants of the gods, who

internally also had levels or classes, the wꜥb or pure ones who seem to have been lower in rank,

specialised priests such as stolists (dressers), lectors (readers), mortuary

priests, horologues (hour-keepers), astronomers, and auxiliary personnel who

may or may not have also been seen as priests (fig. 5). Then there were other priests of very

specific titles where it is also mentioned what rank they had. There were the

‘pure ones of Sekhmet’ and the ‘scorpion charmers’ for instance, in whose job

descriptions it is specifically mentioned that they had the same rank as the

high priest, or the ‘first servant of the god’.

|

| Fig. 5: Specialist priests (W867) |

Try to picture this next time you visit an ancient

Egyptian temple—you can try and look through the veil of time, from the

majestic silent sentinels that remain, to the vibrant hub of activity it must

have been in its heyday.