This past week has been quite an exciting and fun time at the Egypt Centre. On Monday, I joined the museum’s new Collections Access Manager, Meg Gundlach, and colleagues from the Richard Burton Archives at Swansea University in receiving training on using two newly purchased Artec 3D scanners. The training was delivered by Alex Chung, of Central Scanning Ltd. 3D Scanning is a fast and efficient process used to collect 3D point cloud data, for the creation of 3-dimensional models. These are particularly useful as they allow researchers to interact with the Egypt Centre collection in ways that is not always possible through 2D imagery. Additionally, with the creation of 3D models, it is possible to print replicas of our objects, something we plan to experiment with in the coming weeks.

|

| Fig. 1: Alex Chung scanning the Djedhor the Saviour statue base |

During the training, Alex introduced us first to the Artec Eva

scanner, which is designed for larger objects. This structured-light 3D scanner

is the ideal choice for making quick, textured, and accurate 3D models of larger-sized

objects such as a coffin. It scans quickly, capturing precise measurements in

high resolution. We decided to scan the plaster cast of the statue base of

Djedhor the Saviour (W302), which had recently returned to the Egypt Centre following

conservation work at Cardiff Conservation Department (fig. 1). While the exterior

surface was generally straightforward to capture, the interior was quite

challenging. This is because the cast is built around a wooden structure, which

contains some hard-to-reach areas (fig. 2). However, with a little persistence, it

should be possible to capture the entire surface. We then moved on to the Artec

Spider scanner, which is perfect for capturing small objects.

|

| Fig. 2: Scanning the underside of the Djedhor statue base. |

There were several things I was very surprised about. Firstly, both hand-held scanners are extremely light, weighing less than 1kg each. Secondly, just how quickly it takes to scan an object (depending on size, of course). Thirdly, the software package, Artec Studio 17 Professional, is very easy to use. For smaller objects, it only took us on average of 30 minutes to scan, process, and upload the model to Sketchfab—processing times will, of course, differ for each person depending on the processing capabilities of their computers.

|

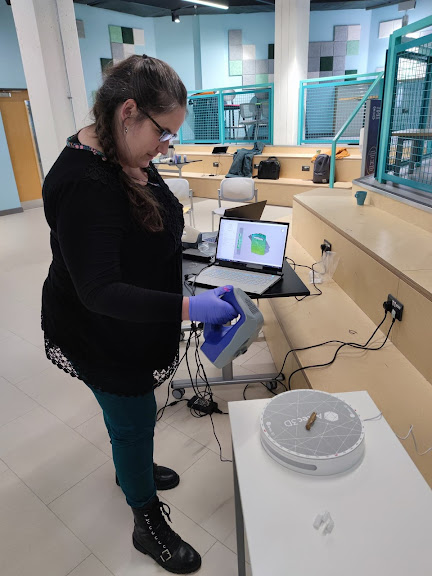

| Meg scanning the amulet of Sopdu-Hor |

Between Tuesday and Friday, we scanned eleven objects. While

still experimenting and getting used to the scanner and software, we are really

happy with the models so far. Some of them were relatively straightforward,

such as the wooden ba-bird (W429), a wooden funerary figure (W453), and

a Cypriot horse (W229a), while others were a little more complicated (fig 3). For

example, PM18 is a very small amulet of a deity, who can be identified as Sopdu-hor thanks

to the inscription on the back pillar. Measuring only 61mm in height, the

scanner often had problems tracking the amulet on the turntable. Additionally,

the inscription isn’t as clear on the models as I would like. However, the main

purpose of the scanners is not necessarily to produce high-resolution textured

images, but to make highly accurate models. The accompanying software actually

allows users to incorporate photogrammetry into the models, which will produce

high-resolution textured models. While we have yet to experiment with this, it

is something that we will be doing over the coming weeks and months.

|

| Fig. 3: Sketchfab image of the ba-bird |

Five objects we did prioritise scanning this week are those

that are currently being used by students in their Egyptian Archaeology module.

Over five handling sessions at the Egypt Centre, the students in this module

get to handle their objects, researching their life history. These objects are

all pottery, including a black-topped redware jar (EC89), a tall cylindrical

jar (AB91), and a small vessel closed by textile (W1287). This latter object

appears to be a rattle, as the students quickly determined (fig. 4). The rattle was very

easy to scan as it had a closed mouth. With the other four pots, scanning the

interiors was difficult. In particular, with EC329 it was impossible to

completely capture because of the closed form of the vessel. We also

experimented with scanning a blue-painted pottery sherd (EC1369) from Amarna, which

was excavated by the Egypt Exploration Society during the 1920s. This is one of

many fragments from Amarna, which will be the focus of an undergraduate

dissertation by Katie Morton. All of our 3D objects are now available on the Egypt Centre's Sketchfab page, where more will be added in due course.

|

| Fig. 4: Christian Knoblauch discussing the rattle with students |

There is still a lot more to learn until we have mastered the various techniques and features. For example, one we were briefly shown at the end of the training was creating inverted object moulds, which can then be 3D printed. This will be particularly useful for school/workshop activities using casts of the Egypt Centre’s objects.

We are grateful to Alex for leading us through the training

and for answering the many questions that we had. Thanks also to our colleagues

in Archives and Academic Services for arranging the purchase of these scanners,

which will really increase public and student engagement of the Egypt Centre collection!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)